CVA Medical Abbreviation

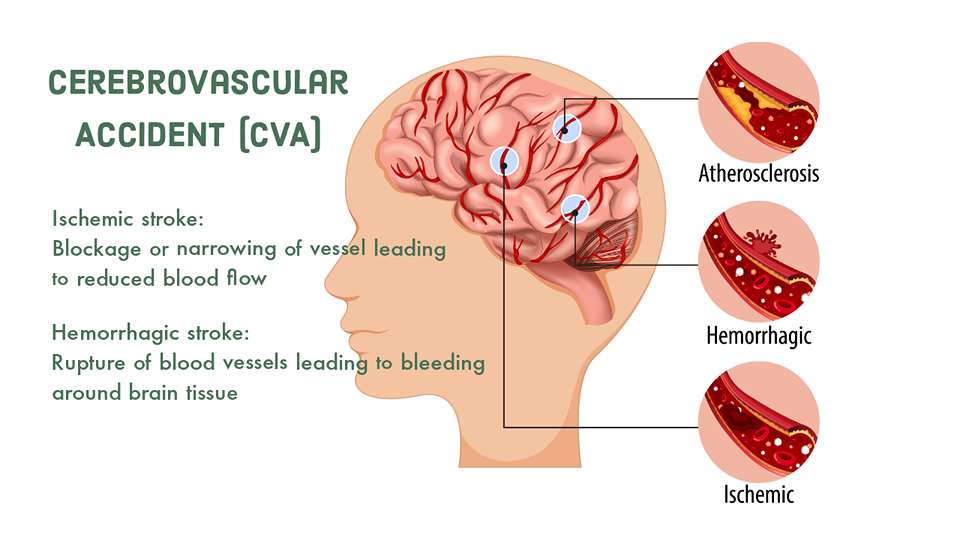

The medical abbreviation of CVA is Cerebrovascular accident. Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) also known as stroke is defined as a rapidly developing focal or neurological deficit due to the vascular cause lasting for more than 24 hrs. A stroke requires rapid diagnosis and treatment as it is a medical emergency. Remember that " time is brain".

This medical abbreviation CVA (cerebrovascular accident) refers to stroke. Apart from Cerebrovascular accident (CVA), there are other CVA medical abbreviation meanings. Among the different meanings of the CVA abbreviation, Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is the most common one & mostly used. CBG is the common medical abbreviation for Capillary Blood Glucose Monitoring used in medical terms.

Classification of Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA)/Stroke

1. Based on the vascular system:

- Arterial stroke (99%)

- Venous stroke (1%)

2. Based on pathology

- Ischemic Stroke

- Hemorrhagic Stroke

A. Ischemic Stroke:

Ischemic strokes are the most common type, accounting for about 85% of all strokes. They occur when there is a blockage or narrowing of a blood vessel in the brain, leading to reduced blood flow and oxygen supply to the affected area of the brain.

There are two main subtypes of ischemic strokes:

- Thrombotic Stroke

- Embolic Stroke

1. Thrombotic Stroke:

A thrombotic stroke occurs usually when a blood clot (thrombus) forms within one of the blood vessels mainly arteries supplying blood to the brain. The clot typically develops at the site of atherosclerosis (plaque buildup) within the blood vessel.

2. Embolic Stroke:

In this type, a blood clot or debris (embolus) forms elsewhere in the body (e.g., in the heart or large arteries) and travels through the bloodstream until it becomes lodged in a smaller brain artery, blocking blood flow.

B. Hemorrhagic Stroke:

Approximately 15% of all strokes account for hemorrhagic stroke. They result from the rupture of a blood vessel in the brain, leading to bleeding into or around brain tissue.

There are two main subtypes of hemorrhagic strokes:

- Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH)

- Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH)

- Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA)

1. Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH):

This occurs when a blood vessel within the brain ruptures and causes bleeding directly into the brain tissue. It often happens due to long-standing hypertension (high blood pressure) that weakens the blood vessel walls.

2. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH):

In this type of hemorrhage, bleeding occurs in the space between the brain's surface (cortex) and the arachnoid membrane. SAH is commonly caused by the rupture of an aneurysm, a weakened and bulging area in a blood vessel.

3. Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA):

Although not technically a stroke, a TIA is a temporary episode of neurological symptoms similar to those of a stroke. It occurs due to a brief reduction in blood flow to a part of the brain. The symptoms of a TIA resolve within 24 hours, usually much sooner. A TIA is considered a warning sign of a potential future stroke, and prompt evaluation and management are essential to prevent a full-blown stroke.

Understanding the classification of Cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) / strokes is fundamental for medical students to differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, as their management and treatment strategies differ significantly. Ischemic strokes may be managed with thrombolytic therapy or mechanical thrombectomy to restore blood flow, while hemorrhagic strokes require measures to control bleeding and reduce intracranial pressure.

Furthermore, recognizing the signs and symptoms of a TIA is crucial for early intervention to prevent a future stroke. As a final-year medical student, solidifying your knowledge of stroke classification will help you become a competent and effective physician when encountering stroke patients in clinical practice.

ISCHEMIC STROKE

Risk factors of Ischemic Stroke / Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)

A. Non-Modifiable Risk Factors of Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA):

Non-modifiable risk factors are characteristics or conditions that individuals cannot change or control. While they contribute to an individual's overall stroke risk, they cannot be modified through lifestyle changes. These risk factors include:

1. Age: The risk of stroke increases with age, especially in individuals over 55 years old. Aging is associated with changes in blood vessels and other physiological factors that increase stroke risk.

2. Gender: Men generally have a higher risk of stroke than premenopausal women. However, stroke risk in women increases after menopause.

3. Race and Ethnicity: Some racial and ethnic groups, such as African Americans, have a higher risk of stroke compared to other populations.

4. Family History: Having a family history of stroke or certain cardiovascular diseases can increase an individual's risk.

5. Prior History of Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA): Individuals who have previously experienced a stroke or TIA are at a higher risk of having another stroke.

B. Modifiable Risk Factors of Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA):

Modifiable risk factors are factors that individuals can influence through lifestyle changes or medical interventions. By identifying these risk factors, individuals can significantly reduce their risk of stroke. Modifiable risk factors for Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / ischemic stroke include:

1. Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): High blood pressure is the most significant modifiable risk factor for stroke. Controlling blood pressure through lifestyle changes and medications can greatly reduce stroke risk.

2. Smoking: Cigarette smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke increase the risk of stroke. Quitting smoking can lead to substantial risk reduction.

3. Diabetes Mellitus: Uncontrolled diabetes increases the risk of stroke. Proper management of blood sugar levels is essential in reducing stroke risk.

4. Dyslipidemia: Abnormal levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood contribute to atherosclerosis and increase stroke risk. Managing lipid levels through diet, exercise, and medications can reduce this risk.

5. Physical Inactivity: Leading a sedentary lifestyle is associated with an increased risk of stroke. Regular physical activity helps to lower the risk of stroke.

6. Obesity: Being overweight or obese can contribute to other risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes, thereby increasing stroke risk. Maintaining a healthy weight is important for stroke prevention.

7. Dietary Factors: Poor dietary habits, such as a diet high in saturated fats, salt, and processed foods, can increase stroke risk. Adopting a balanced and healthy diet can help lower this risk.

8. Alcohol Consumption: Heavy and excessive alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of stroke. Moderating alcohol intake or avoiding it altogether is recommended for stroke prevention.

Etiology of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / ischemic stroke:

1. Emboli are the most common etiology of transient ischemic attack / cerebrovascular accident. Possible origins of an embolus include:

- Heart (most common): typically due to the embolization of mural thrombus in patients with arterial fibrillation.

- Internal carotid artery

- Aorta

- Paradoxical: emboli arise from blood clots in the peripheral veins, pass through septal defects (arterial septal defect, a patent foramen ovale, or a pulmonary AV fistula), and reach the brain.

2. Thrombotic stroke: Atherosclerotic plaque may be in the large arteries of the neck (carotid artery disease, which most commonly involves the bifurcation of the common carotid artery) or in medium-sized arteries in the brain usually the middle cerebral artery.

3. Lacunar stroke: Small vessel thrombotic disease

- Causes approximately 20% of all strokes; usually affects subcortical structures (basal ganglia, thalamus, internal capsule, brainstem) and not the cerebral cortex.

- Predisposing factor: a history of HTN is present in 80% to 90% of lacunar infarctions. diabetes is another important risk factor.

- Due to the thickening of the vessel wall, there is a narrowing of the arterial lumen(not by thrombosis)

- The arteries affected include small branches of the middle cerebral artery, the arteries that make up the circle of Willis, and the basilar and vertebral arteries.

- When these small vessels occlude, small infarcts result; when they heal they are called lacunes.

4. Non-vascular causes: examples include low cardiac output and anoxia.

Causes of ischemic stroke/Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)

Ischemic stroke in young patients is relatively less common than in older individuals, but it can still have significant consequences. Identifying the causes of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)/ ischemic stroke in young patients is crucial for final-year medical students, as it requires thorough investigation and management to prevent recurrence and address potential underlying conditions. Here are some of the key causes of ischemic stroke in young patients:

1. Cardioembolism: Cardioembolic strokes occur when a blood clot forms in the heart (often due to conditions like atrial fibrillation, heart valve disorders, or infective endocarditis) and travels to the brain, causing a blockage. Young patients may have structural heart abnormalities, such as patent foramen ovale (PFO), that allow emboli to pass between heart chambers.

2. Cervical Artery Dissection: Dissection of the carotid or vertebral arteries (tearing of the arterial wall) can lead to the formation of blood clots, which can then cause an ischemic stroke. Trauma, underlying connective tissue disorders, or spontaneous dissection can contribute to this condition.

3. Arterial Abnormalities: Young patients may have congenital or acquired abnormalities of brain arteries, such as arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) or moyamoya disease, which can predispose them to ischemic strokes.

4. Vasculitis: Inflammatory conditions that affect blood vessels, such as autoimmune disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus) or vasculitis syndromes, can cause vessel inflammation, narrowing, or occlusion, leading to stroke.

5. Hypercoagulable States: Certain acquired or hereditary hypercoagulable conditions can increase the risk of blood clot formation, including antiphospholipid syndrome, protein C or S deficiencies, Factor V Leiden mutation, and others.

6. Migraine with Aura: Migraine with aura, especially when accompanied by prolonged visual or neurological symptoms, may be associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke.

7. Substance Abuse: Young adults who abuse substances like cocaine, amphetamines, or certain medications may be at higher risk of ischemic stroke due to their effects on blood vessels and clot formation.

8. Infections: Certain infections, such as bacterial endocarditis, can lead to septic emboli that travel to the brain and cause ischemic strokes.

9. Oral Contraceptives and Hormone Replacement Therapy: In some cases, the use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, especially in individuals with other risk factors, can increase the risk of stroke.

10. Cervical Artery Compression Syndromes: Rarely, anatomical variations or structural abnormalities can compress cervical arteries, reducing blood flow and increasing the risk of stroke.

11. Unknown or Cryptogenic Causes: In a significant number of young patients, the underlying cause of ischemic stroke remains unidentified despite extensive evaluation. These cases are classified as cryptogenic strokes.

Due to the complexity and potential severity of ischemic stroke in young patients, a thorough evaluation is essential to determine the underlying cause. This evaluation may include detailed medical history, physical examination, imaging studies (e.g., MRI, MRA, CT angiography), blood tests, and specific investigations based on clinical suspicion.

Ischemic penumbra

Understanding the concept of the ischemic penumbra is crucial as it represents a key therapeutic target in acute stroke management. Let's delve into the ischemic penumbra in the context of stroke pathophysiology:

Definition of Ischemic Penumbra:

The ischemic penumbra refers to the region of brain tissue surrounding the core infarction in an acute ischemic stroke. When a blood vessel supplying the brain is blocked, an area of the brain becomes ischemic (deprived of oxygen and nutrients). The core infarction is the central area of the brain where blood flow is severely reduced or absent, leading to rapid cell death.

However, surrounding the core infarction is the penumbral zone. This area experiences reduced blood flow but is still perfused to some extent, maintaining partial cellular function. The neurons in the penumbra are at risk of irreversible damage but are not yet irreversibly damaged or dead. The ischemic penumbra is considered an "at-risk" tissue that has the potential to recover if blood flow is restored promptly.

Formation of the Ischemic Penumbra:

In the early stages of an ischemic stroke, blood flow is reduced but not completely blocked in the penumbral region. This partial perfusion allows neurons to remain viable but in a dysfunctional state. The brain cells in the penumbra experience an energy crisis due to the lack of oxygen and glucose, leading to impaired cellular metabolism.

Time Sensitivity of the Ischemic Penumbra:

The ischemic penumbra is a time-sensitive entity. If blood flow is not restored within a critical timeframe, the penumbral tissue will progress to infarction, becoming part of the core infarction. The duration of this critical timeframe varies but is generally in the range of a few hours after the onset of the stroke.

Therapeutic Implications:

Recognizing the existence of the ischemic penumbra is essential in acute stroke management. The main goal of treatment is to salvage the penumbral tissue and prevent further expansion of the core infarction. Time-sensitive interventions, such as reperfusion therapies, are used to restore blood flow to the affected area:

• Intravenous thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA):

This medication can be administered within a few hours of symptom onset to dissolve the clot causing the blockage and restore blood flow.

• Mechanical thrombectomy:

In some cases, a specialized procedure is performed to physically remove the clot responsible for the blockage, providing rapid restoration of blood flow.

Imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), play a crucial role in identifying the ischemic penumbra and determining the eligibility for reperfusion therapies.

Understanding the concept of the ischemic penumbra and its role in stroke pathophysiology will equip you, as a final-year medical student, to appreciate the urgency of timely intervention and contribute to better outcomes for stroke patients. Early recognition and appropriate management of acute ischemic stroke are essential to save brain tissue and improve patients' chances of recovery.

Common anatomical locations and their associated clinical manifestations of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / Stroke

Understanding the anatomical localization of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)/ stroke is essential for medical students, as it allows for a more precise diagnosis and management of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)/ stroke patients. Depending on the affected area of the brain, Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / stroke patients can present with different neurological deficits. Let's explore some common anatomical locations and their associated clinical manifestations:

1. Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) Stroke (cerebral hemisphere lateral aspect): The middle cerebral artery is one of the major arteries supplying the brain and is the most commonly affected vessel in stroke. Depending on whether the left or right MCA is involved, the symptoms can differ:

• Left MCA Stroke: A left MCA stroke often leads to right-sided weakness or paralysis (hemiparesis or hemiplegia), along with language deficits, such as aphasia (difficulty in speaking or understanding language). Patients may also have difficulty with writing (agraphia) and reading (alexia).

• Right MCA Stroke: A right MCA stroke typically results in left-sided weakness or paralysis, as well as neglect of the left side of the body or the environment (hemispatial neglect). Patients may also experience changes in spatial awareness and visual perception.

2. Anterior Cerebral Artery (ACA) Stroke (cerebral hemisphere medial aspect): The anterior cerebral artery supplies the frontal lobes and the medial surface of the brain. An ACA stroke can lead to the following symptoms:

• Contralateral weakness or paralysis, typically affecting the leg more than the arm.

• Loss of voluntary movement and coordination (abulia).

• Changes in personality and behavior, such as apathy or lack of motivation.

3. Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA) Stroke (cerebral hemisphere posterior aspect): The posterior cerebral artery supplies the occipital lobe, the inferior temporal lobe, and parts of the thalamus and midbrain. A PCA stroke can result in the following manifestations:

• Contralateral visual field deficits, often involving the homonymous hemianopia (loss of half of the visual field) or quadrantanopia (loss of a quarter of the visual field).

• Visual agnosia, an inability to recognize objects despite having an intact vision.

• Memory deficits and other cognitive impairments, particularly if the hippocampus is affected.

4. Vertebrobasilar Artery (VBA) Stroke: The vertebrobasilar artery supplies the brainstem and the cerebellum. A stroke in this area can lead to various neurological deficits, such as:

• Severe dizziness or vertigo.

• Difficulty coordinating movements (ataxia).

• Double vision (diplopia) or other eye movement abnormalities.

• Weakness or paralysis on both sides of the body (bilateral symptoms) if the brainstem is involved.

5. Lacunar Stroke (internal capsule): Lacunar strokes are small infarcts that occur in the deep structures of the brain, such as the basal ganglia, thalamus, or internal capsule. These strokes are usually caused by the occlusion of small penetrating arteries. Common manifestations of lacunar stroke include:

• Pure motor stroke: Isolated weakness or paralysis of the face, arm, or leg on one side of the body.

• Pure sensory stroke: Isolated loss of sensation on one side of the body.

• Ataxic hemiparesis: A combination of weakness and ataxia (lack of coordination) on one side of the body.

It's important to note that the above descriptions provide a general overview, and the clinical manifestations can vary from patient to patient. Additionally, some strokes may involve multiple arterial territories, leading to a combination of symptoms.

Diagnosis of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / Stroke

CLINICAL PRESENTATION of Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA)

HISTORY

Taking a history of a Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) case, it's crucial to focus on specific key points to gather relevant information and make an accurate assessment. Here are the important points in history taking for Cerebrovascular accident (CVA):

1. Onset of Symptoms: Ask the patient or their accompanying person about the exact time when the symptoms began. Determine if the onset was sudden or gradual, as this information is vital for determining the type of stroke and potential treatment options.

2. Description of Symptoms: Inquire about the specific symptoms experienced by the patient. Typical stroke symptoms include sudden weakness or numbness on one side of the body, difficulty speaking or understanding speech, sudden severe headaches, and visual disturbances. Ask the patient to describe each symptom in detail.

3. Medical History: Obtain the patient's medical history, including any pre-existing conditions that might increase the risk of stroke, such as hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, heart disease, previous strokes or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and hyperlipidemia (high cholesterol).

4. Medications and Allergies: Record the patient's current medications, including any anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents. Additionally, inquire about any known allergies to medications.

5. Social History: Ask about the patient's lifestyle habits, including smoking, alcohol consumption, and exercise routines, as these factors can influence stroke risk.

6. Family History: Inquire about the patient's family history of stroke or other vascular diseases, as there might be a genetic predisposition to stroke risk.

7. Recent Events or Trauma: Ask if the patient experienced any recent trauma, falls, or injuries that could be related to the current symptoms.

8. Duration and Progression of Symptoms: Document the duration of the symptoms and any changes in their intensity or progression since onset. Note if there have been episodes of improvement or worsening.

9. Associated Symptoms: Ask about any other symptoms associated with the stroke presentation, such as dizziness, balance problems, or loss of consciousness.

10. Time Course: Inquire about the time course of the symptoms, including any fluctuations or patterns of symptom occurrence.

11. Witness Information: If possible, gather information from witnesses or family members who were present when the symptoms started, as they may provide valuable details about the initial presentation.

12. Last Known Well (LKWS): Determine the time when the patient was last known to be without stroke symptoms. This information is crucial for making time-sensitive treatment decisions, particularly for reperfusion therapies like thrombolytic therapy.

13. Other Medical Conditions and Risk Factors: Ask about any other medical conditions or risk factors that could contribute to stroke risk, such as obesity, sedentary lifestyle, sleep apnea, or a history of migraines.

Taking a detailed and organized history of a stroke case is essential for formulating a differential diagnosis, understanding the potential cause of the stroke, and planning appropriate management and treatment. Practicing history-taking skills during your clinical rotations will help you become proficient in identifying and managing stroke patients effectively.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION in Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)

When evaluating a stroke patient, The examination should be systematic and focused on identifying neurological deficits and potential underlying causes of the stroke. Here are the key components of the physical examination of a stroke patient:

1. Neurological Assessment:

• Mental Status: Evaluate the patient's level of consciousness, orientation, and cognitive function.

• Cranial Nerves: Assess each cranial nerve function, including visual acuity, extraocular movements, facial symmetry, and gag reflex.

• Motor Function: Test muscle strength and tone in all four limbs. Look for any asymmetry or weakness, which is often contralateral to the affected side of the brain.

• Sensory Function: Evaluate sensory perception, including touch, pain, and proprioception, on both sides of the body.

• Coordination and Balance: Assess the patient's gait, coordination, and balance. Look for signs of ataxia or other abnormalities.

• Reflexes: Test deep tendon reflexes, including the biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, patellar, and Achilles reflexes. Absent or exaggerated reflexes may indicate specific stroke syndromes.

• Plantar Reflex: Perform a Babinski reflex test to assess the plantar response. an upper motor neuron lesion is indicated by a positive Babinski sign.

2. Cardiovascular Examination:

• Blood Pressure: Measure the patient's blood pressure in both arms to identify any discrepancies.

• Heart Auscultation: Listen to the heart sounds to identify any potential cardiac sources of emboli, such as atrial fibrillation or valvular abnormalities.

3. Respiratory Examination:

• Lung Auscultation: Listen to lung sounds to exclude any respiratory conditions that may mimic stroke symptoms.

4. Skin Examination:

• Check for any skin abnormalities, rashes, or signs of infective endocarditis, which can be a potential source of emboli causing stroke.

5. Head and Neck Examination:

• Examine the head for signs of trauma or injury that may contribute to the patient's presentation.

• Palpate the carotid arteries for bruits, which may indicate carotid artery stenosis.

6. Abdominal Examination:

• Perform an abdominal examination to assess for any potential sources of emboli, such as atrial myxoma.

7. Extremities Examination:

• Look for any signs of deep vein thrombosis or emboli originating from the lower extremities.

It is essential for medical students to practice and refine their neurological examination skills to detect subtle neurological deficits accurately. Familiarity with the components of the physical examination in stroke patients will aid in localizing the stroke's location, identifying potential underlying causes, and guiding appropriate management and treatment plans.

Differential diagnosis of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / Stroke and transient ischemic attack

A. "Structural" stroke mimics

- Primary cerebral tumors

- Metastatic cerebral tumors

- Subdural hematoma

- Cerebral abscess

- Peripheral nerve lesions

- Demyelination

B. "FUNCTIONAL" stroke mimics

- Todds paresis (after epileptic seizure)

- Hypoglycemia

- Migrainous aura (with or without headache)

- Focal seizures

- Meniere's disease

- Conversion disorder

- Encephalitis

Investigations for Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / Stroke

Investigating a patient with an acute Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / Stroke requires a systematic approach to diagnose the type of stroke, identify its cause, and determine the most appropriate management. Here are the key investigations for a patient with an acute stroke:

1. Neurological Assessment: Perform a thorough neurological examination to assess the patient's level of consciousness, cranial nerve function, motor strength, sensation, coordination, reflexes, and any other neurological deficits. This assessment will help localize the stroke and determine its severity.

2. Imaging Studies:

a. Non-Contrast Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: A non-contrast CT scan of the brain is typically the initial imaging study to differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. It helps identify the presence of acute bleeding, assess early changes of ischemia, and rule out other intracranial pathologies.

b. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI): An MRI with DWI is more sensitive than CT in detecting early ischemic changes and can help identify small or lacunar infarctions.

3. Vascular Imaging:

a. Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) or Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA): These imaging studies assess the blood vessels of the head and neck to identify occlusions or stenosis, providing valuable information about the underlying vascular pathology.

b. Carotid Ultrasound: This study assesses the carotid arteries to detect any stenosis or plaques that might be the source of emboli causing the stroke.

4. Laboratory Investigations: a. Complete Blood Count (CBC): To assess for anemia and platelet levels. b. Blood Glucose: To rule out hyperglycemia, which can mimic stroke symptoms. c. Electrolytes and Renal Function Tests: To evaluate metabolic status and assess for potential complications. d. Coagulation Profile: Including PT (prothrombin time) and aPTT (activated partial thromboplastin time) to screen for coagulation abnormalities. e. Lipid Profile: To assess lipid levels and cardiovascular risk factors. f. Cardiac Markers: Such as troponin to evaluate cardiac function and identify potential cardiac sources of emboli.

5. ECG (Electrocardiogram): An ECG is essential to identify cardiac arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, or other abnormalities that may be associated with the stroke or predispose the patient to embolic events.

6. Chest X-ray: A chest X-ray can help identify any underlying respiratory or cardiac conditions that may have contributed to the stroke.

7. Other Specific Investigations: Depending on the clinical context, the following investigations may also be considered:

• Echocardiogram: To assess cardiac function and identify potential cardiac sources of emboli.

• Thrombophilia Screening: If there is a suspicion of underlying hypercoagulable states.

Remember that the investigations required may vary based on the patient's clinical presentation and the resources available. Interpreting the results of these investigations, along with a detailed clinical history and examination, will help you establish a precise diagnosis, determine the stroke subtype, and guide appropriate management and treatment for the patient.

MANAGEMENT OF Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / STROKE

A. SUPPORTIVE CARE in Cerebrovascular accident (CVA):

1. AIRWAY: Perform bedside swallow screen and keep patient nill by mouth if swallowing is unsafe or aspiration occurs.

2. BREATHING: CHECK RESPIRATORY RATE AND OXYGEN SATURATION AND OXYGEN IF SATURATION <95%

3. CIRCULATION: Check peripheral perfusion, pulse, and blood pressure and treat abnormalities with fluid replacement, anti-arrhythmic and inotropic drugs as appropriate.

4. HYDRATION: If signs of dehydration, give fluids parenterally or by nasogastric tube.

5. NUTRITION

- Assess nutritional status and provide nutritional supplements if necessary

- If dysphagia persists for .48 hrs, start feeding via a nasogastric tube.

6. MEDICATION: IF THE PATIENT IS DYSPHAGIC, CONSIDER ALTERNATIVE ROUTES FOR ESSENTIAL MEDICATIONS.

7. BLOOD PRESSURE

- Unless there is heart or renal failure or evidence of hypertensive encephalopathy or aortic dissection, do not lower blood pressure in the first week as it may reduce cerebral perfusion.

- Blood pressure often returns to the patient normal level within the first few days.

8. BLOOD GLUCOSE

- Check blood glucose and treat when levels are > 11.1 mmol/l (200mg/dl)

- Monitor closely to avoid hypoglycemia.

9. TEMPERATURE

- Investigate and treat the underlying cause if pyrexic

- Control with antipyretics, as raised brain temperature may increase infarct volume.

10. PRESSURE AREAS:

Reduce the risk of skin breakdown:

- Treat infection

- Maintain nutrition

- Provide pressure-relieving mattress

- Turn immobile patients regularly

11. INCONTINENCE

CHECK FOR CONSTIPATION AND URINARY RETENTION; TREAT APPROPRIATELY. Avoid urinary catheterization unless the patient is in acute urinary retention or incontinence is threatening pressure areas.

12. MOBILIZATION: Avoid bed rest

B. SPECIFIC TREATMENT of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)

A. INTRAVENOUS THROMBOLYSIS

Intravenous administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-tPA), within three hours of the onset of symptoms reduces disability and mortality from ischemic stroke.

Indications for r-tPA:

- Clinical diagnosis of stroke

- CT scan showing no hemorrhage or infarct size in more than one-third of the MCA territory

- Onset of symptom to time of drug administration less than or equal to 3 hrs (time window: 3-4.5 hrs)

- Consent by patient or surrogate

- Age more than or equal to 18 yrs.

Major contraindications for rt-PA administration:

1. Hemorrhagic Stroke: Rt-PA is absolutely contraindicated in patients with any evidence of intracranial hemorrhage on brain imaging (CT or MRI). Administering rt-PA in such cases can worsen the bleeding and lead to catastrophic outcomes.

2. Significant Head Trauma or Prior Stroke within 3 Months: Patients with a history of significant head trauma or previous stroke within the past three months are at increased risk of bleeding complications and should not receive rt-PA.

3. History of Intracranial Hemorrhage: Patients with a history of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage at any time in the past should not be given rt-PA due to the high risk of rebleeding.

4. Suspected Aortic Dissection: Rt-PA is contraindicated in patients suspected to have aortic dissection, as thrombolysis can exacerbate the condition.

5. Active Bleeding or Bleeding Diathesis: Patients with active bleeding, recent major surgery (within the past 3 weeks), or a known bleeding diathesis (e.g., hemophilia, severe thrombocytopenia) should not receive rt-PA.

6. Uncontrolled Hypertension: Patients with severely elevated blood pressure (systolic > 185 mmHg or diastolic > 110 mmHg) are at higher risk of bleeding complications and should have their blood pressure adequately controlled before considering rt-PA administration.

7. Rapidly Improving or Minor Stroke Symptoms: Rt-PA is not indicated in patients whose stroke symptoms are rapidly improving or are minor (i.e., the patient has little or no neurological deficit at baseline).

8. Use of Oral Anticoagulants: Patients taking oral anticoagulants, such as warfarin, with an international normalized ratio (INR) above the therapeutic range, are at an increased risk of bleeding and are generally not eligible for rt-PA.

9. Blood Glucose < 50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L): Patients with severe hypoglycemia at the time of presentation are at risk of neurological deficits that mimic stroke symptoms. Hypoglycemia should be corrected before considering rt-PA.

It is essential for medical students to recognize these contraindications when assessing stroke patients for potential rt-PA treatment. Rapid and accurate identification of eligible candidates is critical for timely stroke management and improved patient outcomes. As always, decisions regarding stroke treatment should be made in consultation with experienced clinicians and adhere to established stroke treatment guidelines.

• ADMINISTRATION:

Administer at the rate of 0.9 mg/kg intravenously (max. 90 mg) as 10% of the total dose as an intravenous bolus and the remainder of the dose as a continuous intravenous infusion over 60 min.

- No other antithrombotic treatment for 24 hrs

- Avoid urethral catheterization for 2 hrs.

- Stop the infusion, give cryoprecipitate, and re-image the brain emergently for the decline in neurologic status or uncontrolled blood pressure

B. ENDOVASCULAR MECHANICAL THROMBECTOMY

It is an alternative or adjunctive treatment of acute stroke in patients who are ineligible for or have contraindications to thrombolytics or in those who have failed to have vascular recanalization with thrombolytics.

C. ANTITHROMBOTIC TREATMENT AND STATINS

a. Platelet inhibition: Aspirin, Clopidogrel

- Aspirin reduces atherosclerotic stroke morbidity and mortality and is typically given at an initial dose of 325 mg within 24 to 48 hrs of stroke onset.

- The dose may be reduced to 81 mg in the post-acute stroke period.

- Do not give aspirin if the patient received t-PA (due to an increased risk of ICH)

- If the patient cannot take aspirin give clopidogrel.

b. Anticoagulation: Trials do not support the use of heparin or other anticoagulants for patients with acute stroke (except in the case of cerebral venous thrombosis)

c. Statins: Atorvastatin, Rosuvastatin

D. NEUROPROTECTION

Hypothermia is a powerful neuroprotection treatment.

REHABILITATION

- PROPER REHABILITATION OF THE STROKE PATIENT INCLUDES EARLY PHYSICAL, OCCUPATIONAL, AND SPEECH THERAPY.

- educating the patient and family about the patient's neurologic deficit, preventing the complications of immobility comes (e.g., DVT, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, muscle contractures, pressure sores of the skin ), and providing encouragement and instruction in overcoming the deficit comes under the rehabilitation of stroke patient.

SECONDARY STROKE PREVENTION

- ABCD2 SCORE:

• HELPS IN IDENTIFYING THE STROKE RISK

• A score >6 is a high risk for stroke: need secondary stroke prevention

Features and ABCD2 score useful in assessing Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / Stroke risk

| Clinical features | Score |

| A. Age >60yrs | 1 |

| B. Systolic BP >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP >90 mm Hg | 1 |

| C. Clinical symptoms - Unilateral weakness - Speech disturbance without weakness |

1 2 |

| D. Duration of symptoms - >60 minutes - 10-59 minutes |

2 1 |

| D. Diabetes (oral medication or insulin) | 1 |

Lifestyle Modification for Prevention of Cerebrovascular Accidents (CVA)

Lifestyle changes play a significant role in Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / stroke prevention, recovery, and overall management. Here are some key lifestyle modifications that you should be aware of:

1. Smoking cessation: Advise stroke patients to quit smoking immediately. Smoking is a significant risk factor for stroke, and quitting can significantly reduce the risk of future stroke and improve overall health.

2. Healthy diet: Encourage a balanced diet that is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Reduce the intake of saturated and trans fats, cholesterol, and sodium. A heart-healthy diet can help manage blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight.

3. Physical activity: Encourage regular physical activity tailored to the patient's abilities and medical condition. Engaging in moderate-intensity exercises like walking, swimming, or cycling can help improve cardiovascular health and overall well-being.

4. Weight management: If the patient is overweight or obese, work with them to set realistic weight loss goals. Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight can reduce the risk of stroke recurrence and other comorbidities.

5. Limit alcohol consumption: Excessive alcohol intake can raise blood pressure and increase the risk of stroke. Encourage moderate alcohol consumption or complete abstinence, depending on the patient's health status.

6. Manage chronic conditions: Help patients effectively manage chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol. Properly controlling these conditions can significantly reduce the risk of recurrent strokes.

7. Medication adherence: Ensure that stroke patients adhere to their prescribed medications, such as antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, blood pressure medications, and lipid-lowering drugs. Compliance is crucial for secondary stroke prevention.

8. Stress management: Assist patients in identifying and managing stressors in their lives. Chronic stress can negatively impact cardiovascular health and overall well-being.

9. Regular medical follow-up: Stress the importance of regular follow-up appointments with healthcare providers to monitor progress, adjust medications if necessary, and address any concerns or questions the patient may have.

10. Educate the patient's support system: Involve family members and caregivers in the patient's care plan. Educate them about lifestyle modifications, medication adherence, and warning signs of stroke recurrence.

Remember, lifestyle modifications should be individualized and tailored to each patient's specific needs and abilities. As a medical student, you can play a crucial role in counseling stroke patients about the significance of these lifestyle changes, reinforcing the message given by physicians and other healthcare providers.

Complications of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / Stroke

Complications can arise during the acute phase of a Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)/stroke or during the recovery and rehabilitation process. Here are some common complications of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and their management:

1. Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH): In some cases, strokes can lead to bleeding in the brain (intracranial hemorrhage) rather than a blood clot. Management of ICH involves close monitoring in an intensive care setting, blood pressure control, and, if necessary, surgical intervention to relieve pressure on the brain.

2. Cerebral Edema: Swelling of the brain can occur after a stroke, leading to increased intracranial pressure. Management includes elevating the head of the bed, maintaining adequate oxygenation, and administering medications such as diuretics to reduce swelling.

3. Seizures: Some stroke patients may experience seizures. Antiepileptic medications can help control and prevent further seizures. Ensuring a safe environment to prevent injury during a seizure is also important.

4. Aspiration Pneumonia: Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) is common in stroke patients and can lead to aspiration pneumonia. Patients at risk should have a swallowing assessment, and if necessary, be given a modified diet or feeding through a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube.

5. Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Immobility after a stroke can increase the risk of DVT. Preventive measures such as early mobilization, compression stockings, and anticoagulant medications are essential.

6. Pressure Ulcers: Patients who are bedridden or have limited mobility are at risk of developing pressure ulcers. Frequent repositioning, adequate nutrition, and proper skin care are crucial in preventing pressure sore formation.

7. Depression and Emotional Issues: Many stroke patients may experience depression or emotional challenges during their recovery. Recognizing and addressing these issues through counseling, support groups, and, if necessary, medication can be beneficial.\

8. Spasticity: Some patients may develop muscle spasticity, causing stiffness and discomfort. Physical therapy, stretching exercises, and muscle relaxants can help manage spasticity.

9. Urinary Incontinence: Stroke can affect bladder control. Proper evaluation and management, including bladder training and pelvic floor exercises, can be beneficial.

10. Cognitive Impairment: A stroke may cause cognitive deficits. Cognitive rehabilitation, occupational therapy, and speech therapy can aid in addressing these issues.

11. Gastrointestinal Disturbances: Patients may experience constipation or bowel incontinence. Adequate hydration, dietary modifications, and medications can help manage gastrointestinal symptoms.

12. Communication Difficulties: Some stroke patients may have difficulty speaking or understanding language (aphasia). improving communication skills can be assisted by speech therapy.

13. Functional Impairment: Physical and occupational therapy plays a crucial role in helping stroke patients regain functional independence.

It's important to note that stroke management should be individualized, and the approach to complications may vary depending on the patient's overall health status and specific needs.

Paramedical personnel and the general public are taught how to make the diagnosis of Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) / stroke on simple history and examination: @FAST

- F: Face: sudden weakness if the face? ask the person to smile

- A: Arm: sudden weakness or numbness of one arm? ask the person to raise both arms. Does one arm drift downward?

- S: Speech: difficulty in speaking, slurred speech? ask the person to repeat a simple sentence along with you.

- T: Time: sooner the start of treatment, the better the outcome (get to the hospital immediately.

Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA):

A transient ischemic attack, commonly referred to as TIA, is a brief episode of neurological dysfunction caused by a temporary disruption of blood flow to a specific part of the brain. The symptoms and signs of a TIA are similar to those of a stroke, but unlike a stroke, the symptoms of a TIA resolve completely within 24 hours, often within minutes to hours.

Key points about TIA:

1. Duration: The hallmark feature of a TIA is that the symptoms and neurological deficits are transient, lasting for a short period, usually less than 24 hours. Most TIAs resolve within minutes to hours, and rarely they may last up to 24 hours.

2. Symptoms: The symptoms of a TIA can vary depending on the part of the brain affected. Common symptoms may include sudden-onset weakness or numbness in the face, arm, or leg (often on one side of the body), trouble speaking or understanding speech, vision changes, dizziness, and difficulty with balance and coordination.

3. Temporary Nature: The term "transient" in TIA emphasizes the temporary nature of the symptoms, which distinguishes it from a stroke where the symptoms are persistent and may cause permanent neurological deficits.

4. Warning Sign: TIA is often considered a warning sign or precursor to a more severe ischemic stroke. Identifying and managing TIA promptly is essential to prevent a subsequent stroke.

5. Urgent Evaluation: Because of the potential link between TIA and stroke, individuals who experience TIA symptoms should seek immediate medical attention. Evaluation, diagnosis, and management of TIA are similar to that of acute stroke to determine the underlying cause and implement appropriate preventive measures.

Types of transient ischemic attack

- Large artery low flow TIA: recurrent short-lasting episodes of stereotyped symptoms

- Embolic TIA: longer lasting less frequent episodes with varied symptoms

- Lacunar stroke

Treatment of TIA:

If the patient has an ABCD2 score >4 or has 2 recent TIAs (especially within the same territory): advised for secondary prevention of stroke.

HAEMORRHAGIC STROKE

Hemorrhagic stroke is a type of stroke that occurs when there is bleeding into the brain or the spaces surrounding the brain. This bleeding can compress and damage brain tissue, leading to neurological deficits and potentially life-threatening consequences.

Types of Hemorrhagic Stroke:

1. Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH):

• Intracerebral hemorrhage occurs when there is bleeding directly into the brain tissue.

• It is often caused by the rupture of a weakened blood vessel, typically due to long-standing high blood pressure (hypertension) or an underlying vascular abnormality.

• The blood accumulates within the brain, leading to increased intracranial pressure, which can cause further damage to surrounding brain tissue.

2. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH):

• Subarachnoid hemorrhage occurs when there is bleeding into the subarachnoid space, the area between the brain and the thin membranes that cover the brain (meninges).

• The most common cause of SAH is the rupture of an intracranial aneurysm, which is a weakened and ballooned-out area of a blood vessel in the brain.

• The sudden onset of a severe headache, often described as the "worst headache of my life," is a characteristic symptom of SAH.

Risk Factors:

• Hypertension (high blood pressure) is the most significant risk factor for both types of hemorrhagic stroke.

• Other risk factors include advanced age, smoking, heavy alcohol use, drug abuse (particularly cocaine and amphetamines), and certain medical conditions that affect blood clotting.

Clinical Presentation:

• Depending on the location and size of the bleeding symptoms of hemorrhagic stroke can vary. They may include sudden-onset severe headaches, neurological deficits such as weakness or numbness on one side of the body, difficulty speaking, vision disturbances, and loss of consciousness.

• Subarachnoid hemorrhage often presents with a sudden and severe headache.

Diagnosis:

• Imaging studies, such as a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are crucial for diagnosing hemorrhagic stroke and determining its location and extent.

Management:

• The management of hemorrhagic stroke involves stabilizing the patient's condition, managing intracranial pressure, and preventing further bleeding.

• Specific treatments depend on the underlying cause of the hemorrhage and the patient's overall medical condition.

Prognosis:

• The prognosis for hemorrhagic stroke varies depending on the location and size of the bleed, the rapidity of intervention, and the patient's overall health.

• Hemorrhagic strokes generally have a higher mortality rate than ischemic strokes.

As a medical student, being able to recognize the signs and symptoms of hemorrhagic stroke and understanding its risk factors and management are essential in providing timely and appropriate care to patients who present with this medical emergency.

Comments (0)